We were exploring the old Spanish Quarter in St. Augustine when it happened. We had just stepped out of a quaint clothing shop and back into the Florida sunshine when my cell phone rang. It was my daughter. The news she delivered was so triggering, I lost my shit and burst into voluble, involuntary tears. I felt overcome with violent emotion. Wails and cries erupted, and I bent over, unable to help myself.

My companion, the poet Carrie Shipers, became concerned and asked what was wrong, but I couldn’t speak. I couldn’t explain, and I couldn’t stop crying. She led me into a sheltered courtyard where I could sit and other members of our party joined us. We were all attending the “Other Words” Conference in November 2013, at Flagler College.

I was not given to crying much at that time, and the outburst surprised me as much as my companions. Sure, I’d been a crybaby as a kid, often weepy and mopey, but I’d outgrown that as I matured and developed other coping strategies. As I got older, I often teared up during happy moments, which made me a sentimental crier by my estimation. I’ve never been able to cry on demand at a funeral or a wedding. When I’m really frustrated, the pressure of tears builds up in my eye ducts and nasal cavities and won’t release. It’s like the tears get stuck and only seep out.

When I burst out crying in public in St. Augustine, I lost control. I was triggered by news of a family member’s new diagnosis of metastatic cancer, given six months to live. It had been six months since my husband died of pancreatic cancer after a three-year fight. The pain of another soul experiencing the trauma of cancer burst out of me. I felt temporarily possessed. Surrounded by compassionate women, I eventually calmed down, though it was a revelatory experience and reminded me of Margery Kempe.

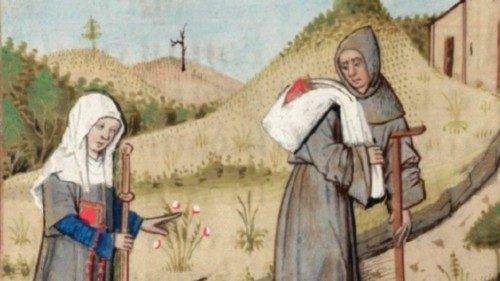

Margery was a medieval religious celebrity who earned her fame through crying. A woman with the gift of tears, she engaged in prolonged public crying jags at home in England and on pilgrimages to the Holy Lands, Rome, and to Santiago de Compostela in Spain. Though she could neither read nor write, her story was written down in vernacular English as told to two scribes, the first who died and left a garbled text, and then a priest to whom Margery told her tale a second time. The manuscript is considered an early form of autobiography, and available in a translation, The Book of Margery Kempe, by John Skinner.

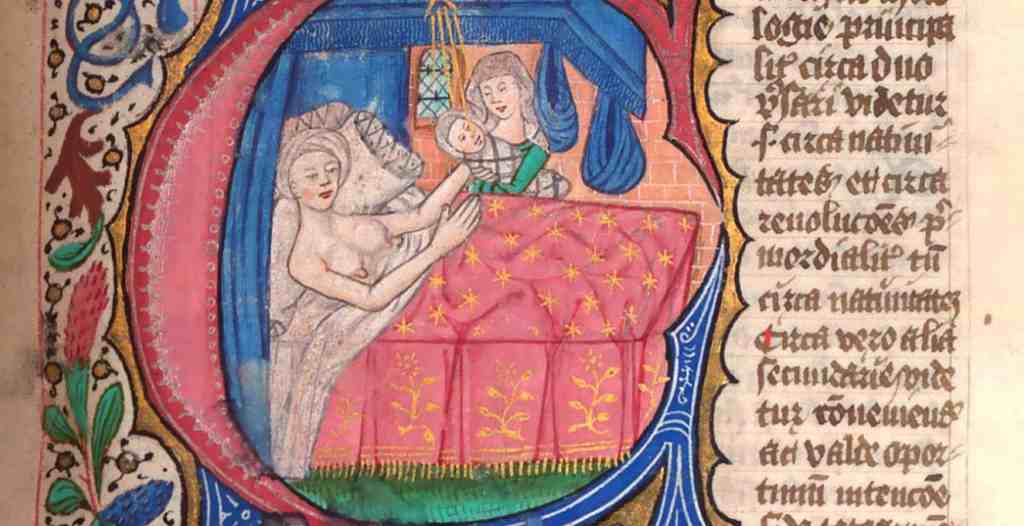

I don’t know if Margery was a “typical” medieval woman, but she has an interesting backstory. Born in 1373, she married and had fourteen children. She ran a brewery for a time before she received the gift of tears. Her father died when she was around forty years old, and she received an inheritance, giving her means. Margery said she cried at first because she “began to realize my own wickedness so that I could only grieve and weep and pray the whole time to be forgiven in his mercy.

It does not surprise me that the gift of tears was accompanied by a Divine command that Margery must become celibate. She’d given birth fourteen times. Her husband wasn’t keen on celibacy and asked, “Margery, supposing a man came along with a sword, and he said he would cut off my head unless I made love to you, tell me truthfully, for I know you never lie, would you let him cut off my head or else would you let me love you, just like I did in the old days?”

Pressed for an answer, Margery replied, “In all honesty, I would rather see you killed than we went back to our old unclean ways.” Her celebrity was growing due to her crying outbursts, and she had the support of some local religious authorities. Ultimately, she agreed to pay off her husband’s debts and eat dinner with him, including meat, and her husband agreed to stop making sexual demands. Margery prayed over the question of meat, and God allowed it, so her vow of chastity was safe.

As Margery’s celebrity spread, she traveled to religious sites in the region around Lynn. When she visited Canterbury, she was so overcome, she wept “almost all day long, morning and afternoon for the sake of the monks and priests as well as for the lay people.” Some church officials were appalled to be lumped with sinners and cried over by the likes of Margery Kempe! She was sometimes accused of being a Lollard, an individual whose divine authority derived from piety and not the Church hierarchy, and more than once she was arrested.

It wasn’t just the authorities who didn’t like Margery. She often infuriated her fellow citizens. When she was on a pilgrimage to the Holy Lands, she was so unpopular that the other travelers gave her “a single noble” and planned to ditch her. Margery explained, “Feelings ran against me throughout our company that I no longer ate meat, and they made sure that my confessor too would be annoyed with me. But they were even more irritated by my continual tears, and the way I would speak openly all the while about the love and goodness of our Lord, both at table when we ate together as well as other places.”

One sympathetic member of the company eventually convinced the others that she should be allowed to continue with them, though they tormented her by cutting her clothes, making her wear a sackcloth apron, and making her sit alone at another table during dinner. Margery’s unrelenting piety was a wet blanket on the party. The medieval pilgrimage, it seems, was akin to a modern vacation package that cost good money and was supposed to be a good time. Margery didn’t care. She was on a mandate from God, and she cried when he commanded it.

Margery’s crying outbursts came and went. They were completely unpredictable. Sometimes she only cried once a month. She recalls, “On one particular day I can remember having fourteen; on another day, seven. It occurred whenever God pleased to visit me in such a way; thus sometimes they would happen in church, sometimes as I was walking along the street, at other times when I was in my room, or in the fields outside. It was always when God chose to send them; I never could guess the time or place.”

To a majority of her contemporaries, Margery was an audible pest, according to her own report. She was a noisy ascetic, who gave away all her money when she was in Rome and encountered extreme poverty. She was said to heal the sick and comfort the dying. She was never ordained a saint, but she also didn’t die by being burned at the stake as a Lollard, a real danger in her time. I admire Margery’s commitment to publicly crying for the sins and evils of the medieval world. Maybe things haven’t changed so much. If Margery Kempe were around today, she’d probably still be crying.

WORKS CITED: Kempe, Margery and John Skinner. The Book of Margery Kempe. Translated by John Skinner, Image Books Doubleday, 1998.

Categories: Good Works, Living, Suzanne's Voice